Study for Self-Portrait

1981

Oil, pastel and dry transfer lettering on canvas

Titled, signed and dated on reverse

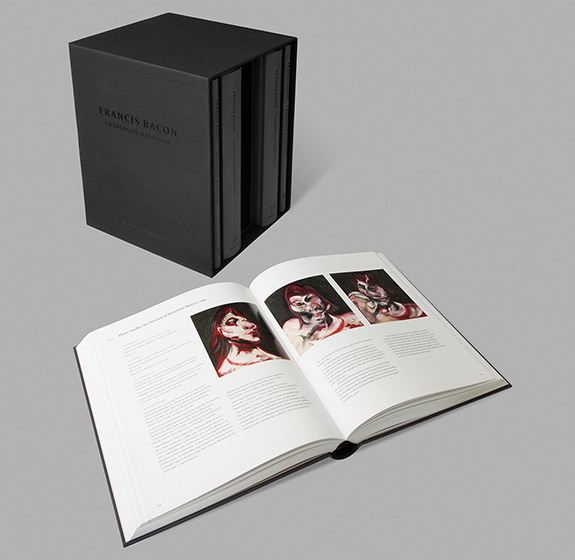

The information in the present section on francis-bacon.com is based on the data in Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné by Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels, which was published by The Estate of Francis Bacon in 2016. The following ‘Notes for readers’ are extracted from the catalogue raisonné (Vol.1, p.102 and 103) and elaborate on the methodology and thinking behind the compilation and presentation of some data, such as titles, dates and media.

Notes for readers

Paintings are catalogued chronologically, under the year of their completion: thus a painting dated 1956-57 will be found in 1957. Undocumented paintings, to which only approximate (circa) dates can be attached, are generally placed at the end of the year in which they are believed to have been painted; this rule is departed from when there is firm evidence that a painting was made at a specific date during a certain year (for example ‘Street Scene (with Car in Distance)’, 1984 (84-03).

Titles of paintings placed in inverted commas, for example ‘Figure with Cricket Pad’, c.1982 (82-09), were not applied by Bacon or by his gallerists, and are merely descriptive. Among the paintings with descriptive titles in the catalogue, many did not emerge into public view until after 1998. Some of the titles initially given to them have been revised here; for example, ‘Figures in a Landscape’, c.1956 (56-11) has been substituted for ‘Two Figures in the Grass’, which is more logical in view of its relationship with Figures in a Landscape, 1956-57 (57-01).

Media

In the past most of Bacon’s paintings have been described as ‘oil on canvas’. But he employed many other media, and was fond of mixing sand, dust, fibres and pastel, for example, with his oils. While every effort has been made to include these details, until paintings are examined (and ideally scientifically tested) with the glass removed, the descriptions of media will inevitably be incomplete.

Dimensions

Canvas dimensions are given in imperial measurements, height preceding width, followed by metric; this conforms with the British manufacture of Bacon’s canvasses.

Signatures

After 1969, Bacon titled, signed and dated, on the reverse of the canvas, a majority of his paintings: before that date he only did so intermittently. It has been our aim to record all such details, but there are almost certainly omissions. The modern practice of fixing backing boards on paintings means that, even when granted privileged access to works, it is not always possible to inspect the reverse side.

Photography dates

Paintings were usually sent to be photographed shortly after leaving Bacon’s studio. The photography dates provide key data, therefore, in the chronology of paintings.

Alley

Alley numbers, for example (Alley 106), are those assigned to each painting in the first catalogue raisonné, Ronald Alley and John Rothenstein, Francis Bacon (London: Thames & Hudson; New York: Viking Press, 1964).

Destroyed paintings

Bacon destroyed many hundreds of paintings. The so-called ‘slashed canvasses’ are not (with one exception, Double Portrait of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, 1964 (64-03)) included in this catalogue. Forty such canvasses, found in Bacon’s studio after he died, are now in Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane. Margarita Cappock published them in 2005 under the heading ‘Destroyed Canvasses’, which raised questions regarding Bacon’s intentions with the destructions. On small portrait canvasses he – or a friend – invariably cut out the head, and on the large canvasses the heads and sufficient of the main figurative elements to nullify the ‘image’ were excised. Doubtless Bacon cut the canvasses so as to leave the stretchers intact for reusage, but while he could not have foreseen the tattered fragments eventually having a commercial value, or being exhibited, he could have rendered the destruction more complete (by burning the fragments, for example). His partial destructions were, typically, ambivalent, while as the creator of images that had ‘failed’, the connotations of violence in his taking a knife to them has clear psychological implications.

Four canvasses removed from Bacon’s studio in 1978 appeared on the market in April 2007, and a further five, from a separate source, were sold in June 2007; six fragments of canvas which had been given in the 1950s to the Cambridge artist Lewis Todd, who painted on their primed sides, were auctioned in March 2013.

Paintings with the suffix ‘D’ in the catalogue (for example 67-15D) are destroyed. Two of these are paintings which had been sold and were destroyed in accidents while in private ownership; a third was damaged beyond restoration when it fell into Tokyo Dock. Other paintings with this suffix in the present catalogue were destroyed by Bacon but had been exhibited publicly before he did so; since images of them are accessible in catalogues, they have been included for the sake of completeness.

In the 1964 catalogue raisonné, under pressure from Bacon, Ronald Alley consigned abandoned or destroyed paintings to two appendixes, classified as ‘A’ and ‘D’. These compromise categories have been jettisoned in the present catalogue, and the extant paintings placed where they occur in the chronology. A compelling reason for ceasing to adopt these categories is that of the nine paintings Alley listed as ‘Destroyed’ in 1964, four in fact survive.

Abandoned paintings

On 30 July 1996 David Sylvester wrote to the then owner of ‘Lying Figure’, c.1953 (53-21), who was disappointed he had not included it in the Bacon retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris. He explained that none of the pictures listed in the 1964 catalogue raisonné as ‘Abandoned’ was treated as a candidate for inclusion, adding ‘it seems reasonable to me that during an artist’s lifetime and for a few years after his death, a retrospective exhibition should not include works that he considered abandoned. I think that a different attitude should be taken when an artist has been dead for some years.’ Sylvester volunteered the comment: ‘As we all know, works which an artist abandoned can still be works of great value: there are any number of such works by a variety of masters in the museums of the world. In my opinion “Lying Figure” is a very fine example of Bacon’s work.’

The question of ‘finish’, as signifying a putative state of completion, is probably less relevant in the case of Bacon than most other artists. An atheist and nihilist, the only ‘finish’ he recognised – and was haunted by – was death: to finish a painting was, perhaps, analogous to dying. It was neither whimsical nor accidental that he called so many of them ‘Study for…’: he was being not so much tentative as open-ended. Moreover, if Fragment of a Crucifixion, 1950 (50-02), in which more than half of the canvas is unpainted, was considered by Bacon a ‘finished’ painting, it is counterintuitive to categorise ‘Lying Figure’, c.1953 (53-21), for example, as ‘unfinished’.

Notes on titles

Robert Melville, reviewing the 1964 Alley/Rothenstein catalogue raisonné in Studio International, July 1964, observed that Study from Innocent X, 1962 (62-2), despite having been painted only two years previously, had already been given three different (if unofficial) titles – Red Pope, Red Pope on Dais, and Red Figure on a Throne. Melville doubted that Bacon gave any of his paintings the title ‘Pope’, and pointed out that when he was working for Erica Brausen at the Hanover Gallery, ‘we used to call them “cardinals” rather than “popes” in the presence of visitors, to make sure that no one would be offended.’ Melville predicted that all the paintings in the 1964 catalogue would be thenceforth known by the titles assigned to them by Ronald Alley. This precept has been adhered to in the present catalogue. Furthermore, for the ‘post-Alley’ years, 1963 to 1991, the titles established by Bacon and Marlborough Fine Art have been adopted consistently; for example, although Painting, 1980 (80-09) was exhibited in 1999 with the descriptive title Three Figures, One with a Shotgun, subsequent research has shown that its original title was Painting, and has been reverted to here.

The five works Bacon included in his first exhibition, in 1930, all had specific titles. In the present catalogue the titles of paintings dating from 1929 and 1930 follow those adopted by Alley, but they have been placed within inverted commas since it is highly unlikely that Bacon titled them as they are, by their media; (Alley had to negotiate Bacon’s indifference – or hostility – towards his pre-1944 œuvre).